British Steel, Scunthorpe and the power of place

Last weekend, something rare happened in Westminster: Parliament was recalled on a Saturday, legislation was rushed through both houses, and by Monday, the government had taken control of British Steel’s Scunthorpe plant – a drastic move to stop the blast furnaces from going cold and, with them, the potential collapse of primary steelmaking in Britain. Losing them would have been a structural blow to our ability to build anything.

The decision to step in was sparked by British Steel’s owners, Jingye, announcing they would shut the furnaces down immediately. That would have meant the loss of more than 2,700 jobs and the end of domestic steel production – a capability the country isn’t ready to lose, especially as demand for steel in construction, transport, and defence only continues to grow. There’s a lot that can (and will) be said about the politics of this. But for those directly involved, the implications are more practical and pressing.

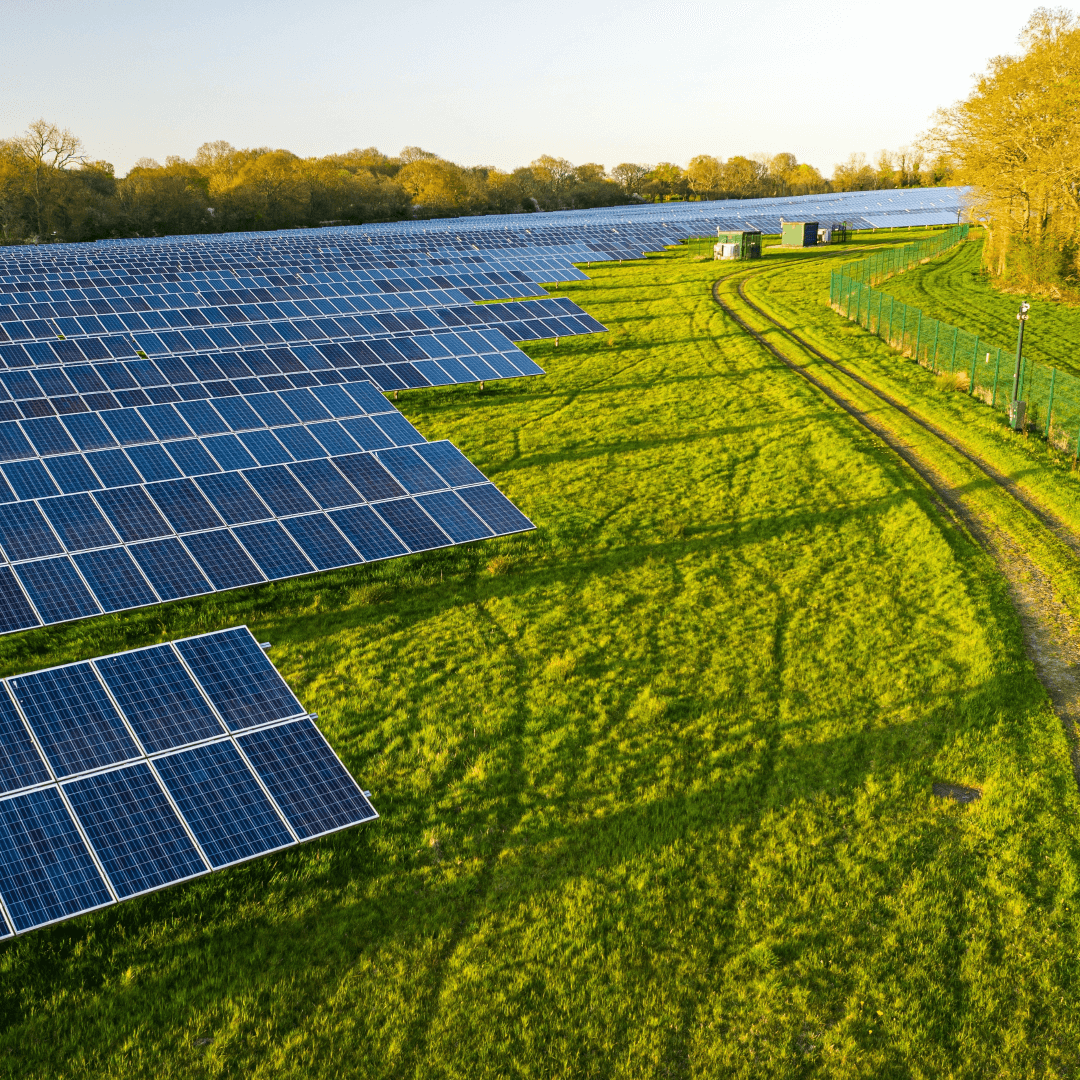

Steel underpins most of the things the government wants to build – housing, railways, energy projects, and roads. Whether it’s the goal to deliver 1.5 million homes or make Britain a clean energy superpower, none of it can happen without the raw materials. The loss of primary steelmaking would leave the country dependent on overseas imports at a time when global supply chains are fragile, and international relations are increasingly tense.

But this is also a deeply local story. For Scunthorpe, this isn’t just about a plant – it’s about identity. The steelworks are part of the town’s DNA, and the economic ecosystem around it stretches far beyond the factory gates. That’s why workers and residents took to the streets. That’s why MPs were dragged back from Easter recess. And that’s why the government moved so quickly. Scunthorpe isn’t just an obscure industrial park – it’s a town defined by steel.

The strength of feeling in Scunthorpe – the protests, marches, and community action – was key to this story. It helped shift the political landscape. Steelworkers, their families and supporters made it impossible for the government to look away. It’s a reminder that economic infrastructure isn’t just about investment zones and freeports – it’s about the places and people who define them.

Local government knows this better than anyone; it’s often the only level of government with the ability to connect economic ambition with the social reality on the ground. That’s why local leadership is going to be essential in whatever comes next, whether it’s nationalisation, restructuring, or a long-term renewal strategy for the plant.

The government stepping in so decisively, effectively overriding foreign corporate ownership to keep the plant running wasn’t just industrial policy – it was a political statement. It’s not business as usual, but a signal that national resilience, whether in manufacturing, energy, transport or housing, is moving up the agenda fast. And it tells councils, regional leaders and local bodies that central government might finally be serious about economic security at the community level, not just in theory, but in action.

This potentially opens the door to a new kind of dialogue between central government and local areas, not just about infrastructure or funding pots, but about strategic assets, industrial land and the kinds of jobs that give places a sense of meaning. It raises the question: if the government is prepared to take back control of steel, what else might now be considered too important to lose?

There’s still a long road ahead. The future of British Steel is still uncertain, and long-term public ownership poses its own set of challenges. But this intervention shows what happens when the politics of power and power of place collide. Scunthorpe may have just helped redefine the role of local places and industry in national policy, and that shift will echo far beyond the blast furnaces.